I will begin by being honest...I have yet to finish a Jane Austen novel in its entirety. While this may seem an heretical statement to be made by a student of English literature I assert that it is the story of the book itself which is more exciting than its contents.

During my undergraduate education I had spent a semester in the UK which in retrospect was the absolute best thing I did during my college education (barring dating my then future wife, of course). Mid-semester our group took a weeklong trip through the English countryside. Our first stop had been the city of Bath in which Austen had spent a great deal of time (according to our guides). This coupled with the fact that we had seen Bride and Prejudice (a Bollywood retelling of Austen's second novel) begun to develop in me a small interest in this enigmatic (to me) author.

On a later day in our journey, after seeing the sun rise on the mysterious Stonehenge and channeling Earth energies at nearby Avebury Henge, we stopped for lunch and a rest in the rural burg of Lacock. I am fairly certain that since 1600 the only thing that has changed in the streets of this small town since is the addition of automobiles and the only change in its bookstore is the dusty cash register used to ring up the ten pounds it cost to purchase the handsome little volume I had excitedly snatched up upon entering.

Maybe I should blame the separation in time periods but as a reader Austen's novels left me questioning what exactly it was about the husband-selction practices of upper middle class Victorian women that made for a rewarding reading experience. The answer was: not much.

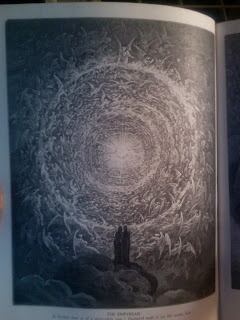

*The illustrations, sadly, tend to reflect the same social distance that makes me dislike the novel (although notice the England train ticket I used as a bookmark, fun!)

I have since made an attempt at finishing Pride and Prejudice and must admit that the characters in this novel were significantly more engaging and multi-dimensional than those in the previous novel, yet time constraints prevented me from reaching the end and memories of a subject matter and societal perspective that I simply cannot connext with have dissolved my motivation to pick up where I had left off.

I am sure that one day I may again pick up the book again and take a stab at Northanger Abbey for I hear it offers a few jabs at the genre of the gothic novel but until then it may remain more of a reminder of good times in the English countryside than the charm of Mr. Darcy.

----

Austen, Jane. The Complete Novels. London, Crown Publishers Inc., 1981.